-

Extrimist Views of National Front in European Parliament.

Introduction

In recent times, the face of European politics has changed. Migrant crisis and terrorism are the everyday topics of all news reports, which consolidate the fear and uncertainty about the future of Europe. Political preferences of the Europeans react accordingly: nationalistic movements are becoming increasingly popular among the population and right-wing parties are getting incredible popularity rates.

In the current work, I would like to have a closer look at the National Front and its politics in the European Parliament. Marine Le Pen or any other right-wing politician is constantly walking on thin ice, especially when talking on the supernational level with a clear national and anti-EU agenda in mind.

The current work aims to analyze Marine Le Pen’s motions for a resolution in the European Parliament and see if they can be categorized as extremist right. I will focus on her speeches starting from June 2014, the period after the European Parliament elections (the National Front got 74 seats) till the beginning of the year 2016. Thematically I will focus on the speeches devoted to the topics of migration as the most representative issue for the right-wing party politicians.For this purpose, I will first give some background about NF and then I will analyze theoretical literature to single out the main features of extreme right politics. I will then analyze Le Pen’s motions for a resolution according to these features and conclude whether their content can be regarded as extremist.

Background

The National Front (Fr. Front National) was founded in 1972 but it has become a political force only after the European Elections in the mid-1980s. However, by the end of the 1980s, there was already established literature attempting to explain the success of the NF (Lubbers, Scheepers 2002).

Some scientists say that from the very beginning, the National Front was an extremist party and it soon became France’s biggest nationalist force. At its essence, the NF is a socially conservative, economically protectionist, and nationalist party. Since the early 1980s, in its politics, it has been targeting immigrants (Griffin 2008) Over the years, Jean-Marie Le Pen, the founder and former leader of the NF has often been accused of his openly xenophobic and anti-Semitic rhetoric. In 1987 for example, he referred to Nazi gas chambers as a “detail of history” (Peter Fysh and Jim Wolfreys 1992). With the shift in power from the controversial figure of Jean-Marie Le Pen to his more moderate daughter, Marine Le Pen the NF has then become legitimized in French politics. From that time on the NF has begun to establish itself as a political force in France as Marine Le Pen has softened the openly racist rhetoric of her father in an attempt to restore the reputation of the NF as a conservative party and get away from its controversial image. In 2013, Le Pen threatened to sue any journalists who referred to her party as “far right” (Todd 2013).

However, the NF is still associated with a xenophobic agenda. Leading up to the 2012 Presidential election, Marine Le Pen made clear her preference for certain immigrant groups over others, “…In the old days, immigrants entered France and blended in. They adopted the French language and traditions. Whereas now entire communities set themselves up within France, governed by their codes and traditions” (Stadelmann 2014). Marine Le Pen got a lot of criticism in 2010 for comparing Muslim prayers in the streets to Nazi occupation (Henderson 2013).

The NF is signified by its hatred of immigrants, particularly Muslim immigrants, having a monocultural, white vision of France. The NF is also known for being skeptical about the EU, but its main focus is still issues of immigration.

Apart from that The NF vaguely promises its electorate to promote the industrialization of France through a protectionist tariff while also increasing military spending, getting rid of privatization of public services, and increasing welfare spending. After taking first place in the 2014 Municipal election, Marine Le Pen declared, “The people want to be protected from globalization” (Abboud, John 2014)

The NF continues to gain popularity. Between the 2007 and 2012 Presidential elections, the NF increased its average vote for the first round of elections in mainland France from 11.2% to 19.1%. In 2014, the NF won the European Parliamentary election under the guidance of Marine Le Pen for the first time. In the 2015 Regional elections, the NF has gained a shocking 27.73% of votes. (Adriana Stephan 2015)Defining an Extremist Party

Thousands of newspaper articles and hundreds of pieces of scholarly work have been devoted to extreme right parties, predominantly describing their history, leaders, or electoral successes, as well as proclaiming their danger. Remarkably little serious attention has been devoted to their ideology, however. This aspect of the extreme right has been considered to be known to everyone. The few scholars who did devote attention to the ideology of the contemporary extreme right parties have primarily been concerned with pointing out similarities with the fascist and National Socialist ideologies of the pre-war period. If the similarities were not found, this was often taken as ‘proof ’ that the extreme right hides its (true) ideologies, rather than as a motivation to look in a different direction. (Mudde 2000)

Measuring a party’s ideology can be really difficult and the majority of scientists still use the Left-Right ideological scale. Initially, there have been two main strategies for placing a party within this scale (a) to rely on opinions, implicit or explicit, of those in a position to make informed judgments on the ideological location of parties in particular national contexts – so-called ‘expert’ judgments, or (b) to use mass survey techniques to see how voters divide up the party system in Left-Right or other terms. However, none of these methods could be truly called scientific. (Castles, Mair 1997)

Scientists have however introduced several different alternative scales which are based on measuring different features of a party family. It is interesting to note that according to a scale suggested by Mair and Muddle the National Front scores 9.8 out of 10 making it Ultra-Right (Castles, Mair 1997). That means that at least a couple of studies have already scientifically proven the National Front to be an extreme right party.

However, before measuring something it is always helpful to define it. The focus of the current work is the concept of right-wing extremism, an ideology composed of a combination of several different and intrinsically complex features, which we should distinguish to further analyze Le Pen’s motions for a resolution.

So what is right-wing extremism? This simple question is difficult to answer in practice. There are tens of different definitions of this notion but still most scientists agree that it is the ideology that makes the core of this concept. The question of how to define the right-wing extremist ideology cannot be answered unequivocally either. To the extent that a consensus exists among the scientists concerned with this field, it is confined to the view that right-wing extremism is an ideology that people are free to fill in as they see fit. (MUDDE 1995)

In his work, Cas Muddle analyzed 26 definitions and descriptions of the right-wing extremist ‘ideology’ taken from different linguistic areas (Dutch, German, and English), to minimize the influence of country-specific features. These definitions were then used to construct an inventory of those features of the right-wing extremist ideology most often mentioned. The following five features were mentioned, in one form or another, by at least half of the authors: nationalism, racism, xenophobia, anti-democracy, and the strong state. (MUDDE 1995)

In his work, Muddle defines the above-mentioned five features as follows:

Nationalism is described as a political doctrine that proclaims the congruence of the political unit, the state, and the cultural unit, the nation. Muddle also uses Koch’s idea of differentiating between two forms of the nationalist political program: homogenisation and external exclusiveness.

On the one hand, it strives for internal homogenization: only people belonging to the X-nation have the right to live within the borders of state X…. On the other hand, there is the drive for external exclusiveness: that is, state X needs to have all people belonging to the X-nation within its borders (Koch 1991)

Racism for Muddle is a view that there are natural and permanent differences between groups of people. He distinguishes between classic racism, the one which focuses on the differences between the races, and new-racism which focuses on the differences between cultures. Muddle refers to the latter as culturism.

Xenophobia is defined as fear, hate, or hostility regarding ‘foreigners’. Muddle also notes that xenophobia is closely connected to the term ethnocentrism which he sees in the German tradition as a specific form of (collective) xenophobia and defines as holding one’s own Volk or nation to be superior to all others.

To define the idea of anti-democracy Muddles refers to the notion of organic Volk where a people are regarded as a living organism. The leader is the heart of the Volk and has absolute power as only a few, and often only one, persons are gifted by nature with the qualities that good leadership requires.

The last feature the strong state is explained with the help of three sub-features: anti-pluralism, law-and-order, and militarism.

Anti-pluralism is seen as a tendency to treat cleavage and ambivalence as illegitimate homogenization.

Law-and-order presupposes strong punishment of those who breach the rules. Solitary confinement must be served under very poor conditions; the ultimate penalty is capital punishment. To maintain order the state must have a strong police force at its disposal.

Militarism means a strong army that needs a lot of manpower and the newest equipment.Method

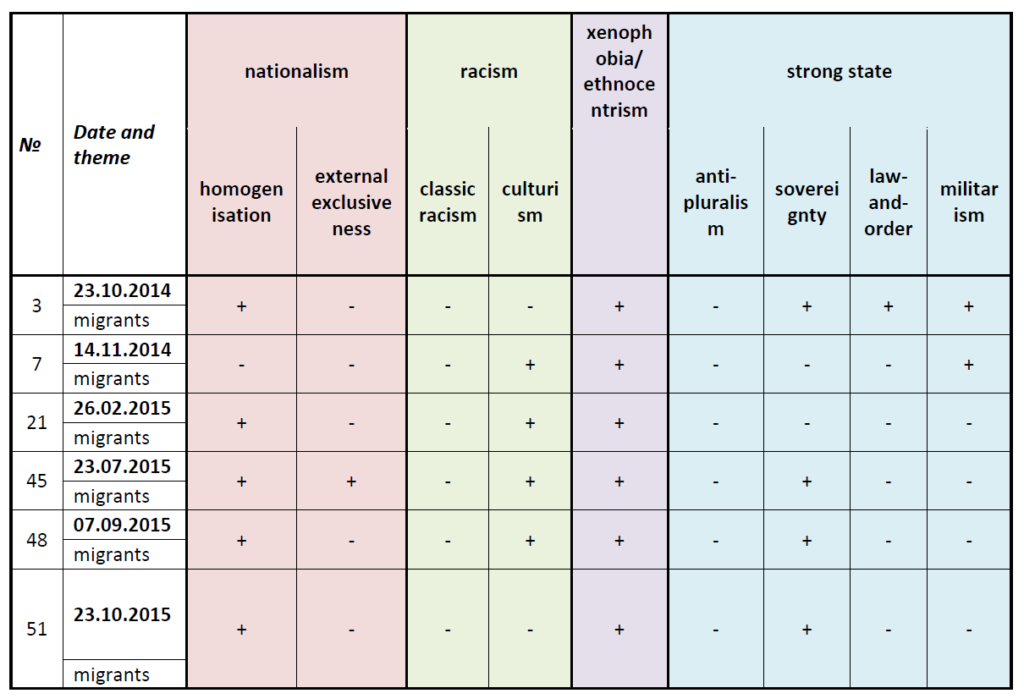

In the current work, I decided to use Muddle’s model to analyze Le Pen’s motions for a resolution. However, I considered it necessary to make some adjustments to this model. As in this paper I am analyzing Marine Le Pen’s politics on the supranational level, it is important to take into consideration, that the inner affairs of every country are not usually discussed in the European Parliament. Thus I excluded a feature anti-democracy as by the definition that Muddle gives this feature concerns the inner affairs of a country.

Another adjustment I made was a sovereignty sub-feature of the strong state feature. Sovereignty presupposes that a country should decide itself about its laws, economic regulation, border control, etc. This sub-feature is also relevant to the EU context.

To test whether motions for a resolution of Le Pen contain the extremist attributes I designed a table where I could test each text on whether or not they contain every particular feature.

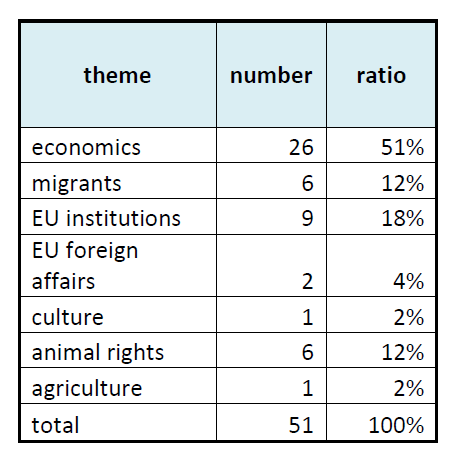

In the period under examination, I found 51 motions for a resolution. In the course of analyses, I singled out 7 thematic groups: economics, migrants, EU institutions, EU foreign affairs, culture, animal rights, and agriculture.

Results

After having analyzed all the texts under analysis I had some interesting findings. In the following table, one can see the allocation of texts within the thematic groups:

As one can see from the table the most frequent theme of Marine Le Pen’s motions for a resolution in the period under analysis is economics (51%). Migrants – the infamous Le Pen’s subject has a ratio of only 12% (!) the same as animal rights.

There were no extremist features found in the texts on such topics as culture or animal rights.

As expected, extremist features were also hardly present in the motions devoted to such topics as economics or EU institutions. The only feature being present there was the strong state, sub-feature sovereignty.

In the texts devoted to migrants, on the contrary, the number of extremist features was always high. You can see from the following table that the feature of xenophobia is always present in the texts devoted to migrants. Nationalism and racism are very present as well.

Conclusions

Can we really call the politics of the National Front in the European Parliament extremist?

The answer is not as obvious as initially assumed and the conducted analyses of the selected sexts show that migration is surprisingly not the main topic of Le Pen’s motions for a resolution, at least not in the period under analysis. Most of her motions are devoted to economics, and the only extremist feature to be found in those texts is the strong state-sub feature sovereignty. It proves the theory that extreme right parties tend to lead protectionist economic politics. Marine Le Pen was very vividly Euro-skeptic in her texts, repeatedly suggesting abolishing Schengen agreements and single currency.

As for migration as a topic, she did not write about it as much as one would expect from her, but all the texts had obvious extremist features in them.

For some reason, in her motions for a resolution for a selected period, Marine Le Pen preferred not to write about the immigration problem extensively. Whether it is cautiousness or something else would be an interesting question to be further investigated.

Bibliography- Abboud, Leila; John, Mark (2014): Far-right National Front stuns French elite with EU‘earthquake. In Reuters, 5/25/2014.

- Adriana Stephan (2015): The Rise of the Far Right: A Subregional Analysis of Front National Support in France. New York University.

- Castles, Francis G.; Mair, Peter (1997): Left-Right Political Scales: Some ‘Expert’ Judgments. In European Journal of Political Research 31 (1/2), pp. 147–157. DOI: 10.1023/A:1006874631504.

- European Parliament MEPs. Available online at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/28210/MARINE_LE+PEN_home.html.

- Griffin, R. (2008): The Extreme Right in France. From Petain to Le Pen. In French Studies 62 (3), p. 374. DOI: 10.1093/fs/knn051.

- Henderson, Barney (2013): “Marine Le Pen ‘loses immunity’ over comparing Islamic prayers to Nazioccupation”. In The Telegraph, 6/1/2013.

- Koch, K. (1991): Back to Sarajevo or beyond Trianon? Some thoughts on the problem of nationalism in Eastern Europe.

- Lubbers, Marcel; Scheepers, Peer (2002): French Front National voting. A micro and macro perspective. In Ethnic and Racial Studies 25 (1), pp. 120–149. DOI: 10.1080/01419870120112085.

- Mudde, Cas (2000): The ideology of the extreme right. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- MUDDE, C. A.S. (1995): Right-wing extremism analyzed. In Eur J Political Res 27 (2), pp. 203–224. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1995.tb00636.x.

- Peter Fysh and Jim Wolfreys (1992): Le Pen, the National Front and the Extreme Right in France. Volume 45 Issue 3 July 1992. Oxford (Parliamentary Affairs).

- Stadelmann, Marcus (2014): The Marinisation of France Marine Le Pen and the French National Front. In International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4, No. 10(1);

- Todd, Tony (2013): Don’t call us ‘far right’, says France’s Marine Le Pen. In France 24, 10/4/2013.